First off and happy new year! The following article I pitched in various forms to a number of magazines, all of which expressed interest but ultimately declined. As such, a big thank you to all subscribers for reading, and particularly paying subscribers for helping me justify giving time to sitting down and writing it, even in blog-form.

I try not to go too much into the expectation of news that goes out of its way to be upbeat, or the need to start the year with as much, but for a while I’ve been watching the development of geothermal energy projects in Cornwall, in the West Country of the UK, and it’s been hard not to admire the inescapably positive story taking root.

To begin with, the energy source. Geothermal energy is made from pumping water into hot rocks in the earth’s crust. Steam is made and rises, driving turbines that produce electricity. The volcanic activity around Iceland means that most Icelandic electricity comes from geothermal energy. Turkey, also with abundant hot springs and subterranean thermal activity, has recently become one of the world’s largest growth markets for geothermal. Unlike wind and solar energy, and in common with tidal energy, geothermal energy is predictable (indeed, it is constant), and so adds additional value to the electricity created, because grid operators - unlike with wind and sun - know exactly what electricity is available and when. This predictable energy supply - baseload capacity - is becoming ever more valuable as more variable renewables come into Western electricity networks.

The Cornish geothermal project, United Downs, should anyway be celebrated for providing zero carbon heat and electricity in a first-of-its-kind UK project. Cornwall now has a string of geothermal power stations in the works, a geothermally-heated new dome at the Eden Project ecological attraction, a geothermal swimming pool complex, and a geothermal rum distillery due to come onstream.

While many of these projects are independent, they have all to some extent been made possible by the United Downs work in Cornwall, demonstrating a viable energy source and business model. That’s a great thing.

Heartening though all this may be, the story behind and emanating from the project demonstrates, in my opinion, something more important and perhaps even more impressive.

Financial ecosystems

Aside from the Cornish geothermal sector now getting a growing amount of media attention, my first awareness of United Downs came through the renewable energy crowdfunding platform, Abundance Investments. With investments starting at just a few pounds, Abundance have now raised over £100million of finance for small-scale renewable energy and other projects that reduce emissions; whether through sustainable farming methods or tidal energy development. United Downs, raised over £4million on Abundance, repaying investors a 2% return after drilling delays caused an overrun in the project that impeded completion within the original timeframe (whereupon 12% would have been paid out). Even the lower rate of return offered an improvement on any conventional savings or current accounts, while also funding early work to develop a new renewable energy source in the UK, that has now been proven viable. For all the perils and hype that can come with crowdfunding, this is obviously an example of it working , and allowing environmental progress that mightn’t have been possible without it.

Since the early stage of development, it has been great to see the evolution of the Cornish projects, and the international attention they have generated.

After Abundance investors funded the early-stage and higher-risk exploratory work to establish feasibility at United Downs, Thrive Renewables (formerly within Triodos Bank, one of the most assertive ethical banks you’ll find), stepped-in to provide project finance for building the first power stations with a now-proven heat source. I made a small investment in the Abundance crowdfunder, and bank with Triodos, and so it was gratifying to see how what can feel like small, abstract decisions had cumulatively helped to bring to market an idea that was good and might not otherwise have been possible.

While this interest in the minutiae of financial decisions might be a geekery particular to me, and based on a commitment to the idea that where we make our purchases is a form of power in managed democracies where political choice is illegitimately restricted, my enthusiasm for the work at United Downs was rounded off when some months later I learned that the UK’s foremost renewable-based energy supplier, Ecotricity, had signed a contract to buy for the next decade a 3MW portion of the electricity from the Thrive-funded power stations now under construction.

Ecotricity is avowedly mission-led on climate, has always reinvested significant proportions of profits in developing new renewable capacity, and though it is a thriving company, you consistently get the impression - unlike many ‘green’ providers - that its mission is genuinely at the heart of what it does. One of the few upsides of years as a tenant moving between rental properties in London has been the number of houses I have successfully had move their bill to Ecotricity, where the profits of those bills are best reinvested in the green transition (this position, and it’s only my opinion, might now be being challenged by Ripple Energy, a platform for community-owned renewables).

At the risk of repeating the above, the compounded circumstance of a crowdfunder I backed, a bank I bank with, and an energy company I have paid bills to - all working together to bring in what will be initially 3MW of power (about 12,000 homes’ worth of electricity) and also renewable heat in Cornwall - felt perhaps as close as I’m likely to get to proving to myself the idea that these micro decisions add up to tangible differences.

While switching off low-energy light bulbs every time you go in and out of a room is unlikely to change world energy demand markedly, the individual choices of who we bank and pay our bills with can - as this instance showed - can help shape enormously positive cumulative outcomes that we might not be able to guess at the outset.

Spillovers not spills

But nor, if you’ll bear with me, does it even stop there, and it’s specifically around the involvement of Ecotricity that I feel there is more room to look positively at this development of an ecosystem of interests and choices.

Ecotricity, founded by traveller-turned-CEO, Dale Vince, was one of the few British businesses to back the Labour Party even under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn. (Given that the Labour party’s 2019 manifesto was audited by Friends of the Earth as better for the environment than even the Green Party’s, it remains a crucial question for another time why most other nominally green entities, publications and interest groups felt unwilling and unable to back a political trend that apparently offered so much to the growth of their agenda).

Ecotricity have also demonstrated a willingness to support campaigns outside of the formal political process; most notably making donations to the anti-fracking groups who were so successful, particularly in Lancashire, in shutting-down the nascent UK fracking industry with all its certainties of pollution, and with local communities shouldering all the costs of fracking and no potential upside. This is, relatedly, almost entirely contrary to the small, local businesses that geothermal energy is seemingly helping to nurture in Cornwall - one of the most deprived regions of the UK.

Though political and media establishments do much to shame, criminalise and belittle protest and protesters, protest does work, as the eventual success of shutting-down UK fracking has shown. It is to Ecotricity’s credit that they were willing to put money and reputation where their mouth was in backing the opposition to fracking, which promised to be politically, environmentally but also economically unsafe.

There is a final poetry and validation to the anti-fracking position - and that of sticking to your principles - in that one of the chief fracking outfits in the UK, Third Energy, has since begun to seize on the momentum in geothermal energy and potentially put its subterranean expertise and drilling background to better use, beginning work to develop geothermal opportunities in Yorkshire.

This near-Damascene conversion from a fracking-to-renewables-developer in response to the UK fracking moratorium is also strong evidence for another deliberately downplayed point; industry, rather than being permitted by shady lobbying to set agendas contrary to the public interest, should be set with strict rules of what the public and their representatives will allow, whereupon they become quite capable of deploying their business model in pursuit of better outcomes - in this case geothermal energy. If lobbying for rule changes is the cheapest path to profit, that’s reliably what fossil companies do. Where lobbying is not effective, they are required to spend on productive activity in-line with the laws of a land.

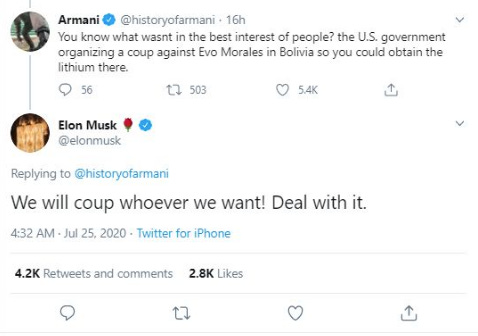

That the subterranean drilling in Cornwall has also discovered substantial lithium supplies, local to the UK and crucial to the development of any domestic industry for electric vehicles, should be seen as an added bonus. When it is considered that Tesla chief, Elon Musk, said of US involvement in the 2019 Bolivia lithium coup “we will coup whoever we want”, it seems safe to say anything that takes Western and corporate pressure off Global South resource producers by opening supplies elsewhere should be welcomed.

In praise of nodes

At every step of this process, what is evident is the development of an ecosystem of political, community and economic actors willing to make decisions that cumulatively benefit the social and environmental good.

Each of these individual standpoints, and the individual decisions behind them, taken in isolation, has limited ability to affect change, but taken together, they become powerful. In this case, an initial 12,000 Cornish homes will get renewable electricity from Cornish geothermal energy. Awareness of this energy source, but also of everyone who works on constructing a power station, or on the now-growing Cornish geothermal sector, further helps make-real to new people the idea of the green economy - its necessity, but also its feasibility.

I find myself thinking at this stage unavoidably of mycelium, the complex structures of fungi that eventually develop to mushrooms, with networks developing around nodes which form foundational points to spread the network.

In the Cornish geothermal case we see nodes of ethical finance, green energy production, and popular movements all combining to fruit a positive outcome in both social and environmental terms. This, in turn, can become another more established node from which further gains can be built.

It is arguably a key feature of what is commonly called late-capitalism that in a setting of rampant consumerism, homogenous media spectacle and political horizons made to appear narrower than they actually are, we as individuals can be left to feel powerless and without consequence. Building nodes that resist the onslaught of each of those limiting factors is both a useful organising philosophy in its own right, but also a reminder that neither our selves nor our decisions exist in isolation.

Taken together, they build the world we want.