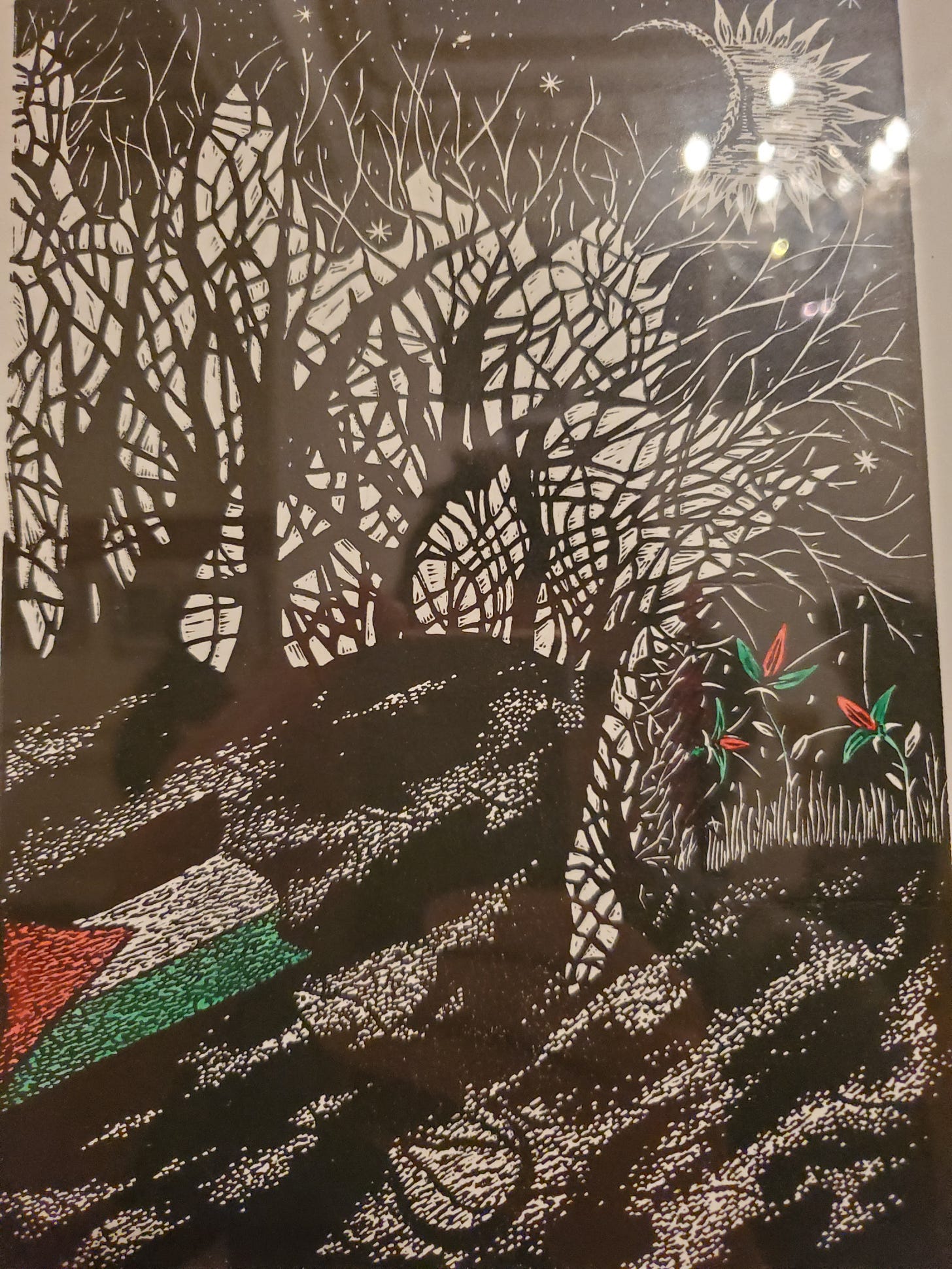

Every year the Embassy of Palestine in Argentina hosts an art exhibition at its building in Buenos Aires. In a meeting prior to it, and with a mixture of pride and some surprise, chargé d'affaires Riyad al-Halabi explained that, where it had originally attracted mostly Argentine artists inspired by Palestine, its reach has since expanded across Latin America, while also this year attracting works from Poland, Czechia, Canada and North Macedonia. Among the global submissions, the work of honour this year is from Palestinian artist Mohammed al-Haj, a Gaza-based painter whose work - depicting a Palestinian protester facing Israeli gunfire with a slingshot - was sent from Gaza last autumn, just before the enclave was further sealed-off from the world, and via a friend in the West Bank who was flying to Argentina anyway.

As the exhibition opens, a recorded video message from al-Haj is played, in which the artist stands in a keffiyeh and in front of olive trees. He thanks the embassy for his invitation and expresses a hope that the killing in Gaza can soon be brought to an end. The video is followed by a reading of the Mahmoud Darwish poem, 'Rita and the rifle', and then an audio interpretation of the poem by a sound designer from the studio next door, who has clearly had his politics shaped by years working next to a Palestinian embassy.

Though far from easy anywhere, the experience of Palestinian politics in Argentina has been harder than that one found elsewhere in Latin America. Argentina does not have the significant movement for indigenous rights that makes the Palestinian one almost intuitive in Bolivia, nor the claim upon a role of Global South ambassador that helps it along in Brazil. It does not have the sizable diaspora numbers of Chile where - at half a million - Palestinians who emigrated before and since the Nakba of 1948 now make up more than 2% of the Chilean electorate, an enfranchisement they are still denied in Palestine.

In other respects, the Chilean and Argentine populations are obliquely connected; Palestinian traders who in the nineteenth century made their way to the major port of Buenos Aires found Syrians already had a strong hold on the garment trade in which they excelled, leaving Palestinians to cross the Andes and begin businesses in Santiago instead. Because Palestinians, Syrians, Lebanese and other Arabs all arrived on Ottoman passports, Argentines often refer to everyone simply as "Turco". Carlos Menem, the most prominent Argentine president of the nineties, was of distant Syrian heritage, and he gave Palestine the empty building that now houses its embassy and exhibition.

The large Jewish population of Argentina, one of the world's biggest outside of Palestine, and by far the largest in Latin America, has long made Zionism an established component of Argentine-Jewish identity, and its organising continues to dominate in Buenos Aires. The election of the new, far-right president, Javier Milei, pledging to follow the US lead in shifting the Argentine embassy to Jerusalem, has done nothing to dull this situation, and much to aid it. Nor has the chance by which a few of the Israeli settlers taken hostage by Hamas happened to be Argentine (including two the Israelis rescued, using a bombing that killed 100 Palestinians, including children, as a “decoy"). Nonetheless a recent collection at the Buenos Aires embassy, raising funds for relief in Gaza, was well-attended. "You can see that Argentine people see what is happening, they are moved", said al-Halabi.

Before leaving the event, I speak with a young Palestinian from Ramallah, studying for a year at a US university but this week on a research trip in Buenos Aires. She confesses to being tired by the last few months, though constantly buoyed and amazed to find how much the world actually does care for Palestine.

I ask if she has been back recently, and she remarks that even Ramallah, ordinarily so sedate, has seen Israeli attacks in the last few months. When even Ramallah is facing raids, you know things are bad. Insisting she wanted to return to her family for holidays in December, she had been advised to delete all apps from her phone. The Israelis have software to unlock people's devices at West Bank checkpoints, where they now scroll through all the photos and social media of Palestinians. She did return, some of her travel companions being detained en route, although she was allowed through. With these invasions of privacy and fundamental freedoms, journey times across the occupied West Bank have doubled in length for Palestinians.

"'Don't give me a reason to shoot you' used to be how it was with the Israelis at checkpoints," she says, "now it's 'give me a reason not to shoot you.'"