A second country then. When riding up Chile I consider that one of the alternative book projects I thought about working on rather than this one would have seen me cycle from the Sahara to the Arctic Circle, a distance that I realise after a few days riding is a little shorter than simply cycling the length of Chile.

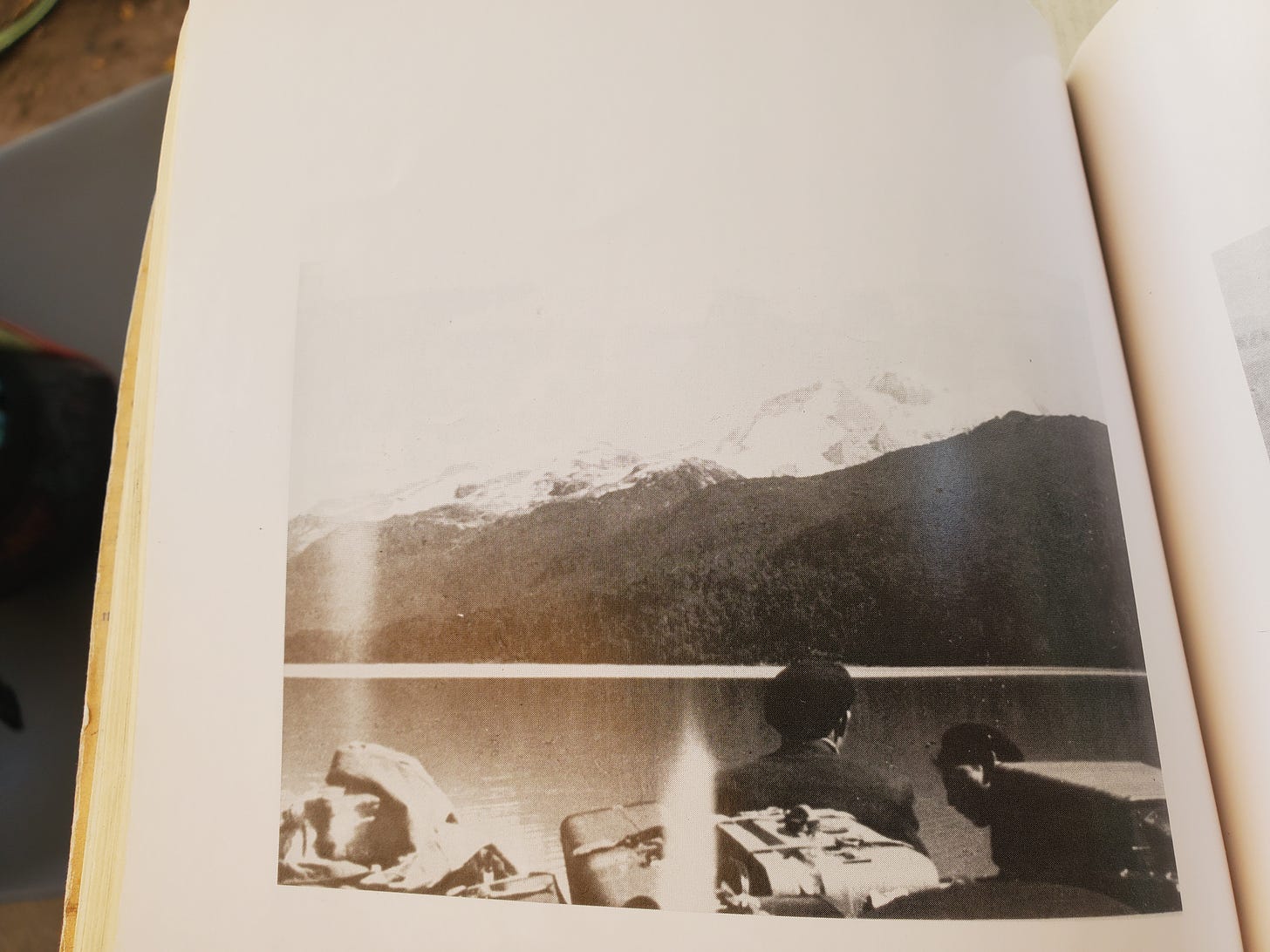

Arrival into the country was more idyllic than much of what has followed. While parts of this journey have and will diverge from The Motorcycle Diaries route of Guevara & Granado, I saved the climbing and altitude effort of cycling across the Andes, and made the logistical effort of combining a boat and a bicycle across three Andean lakes to reproduce the exact route the two friends took into Chile in 1952.

Aside from the similitude of the crossing, Chile has so far been a contrast from Argentina. The wide and open Pampa of the latter, for all its headwinds, emptiness and the logistics of managing both, had in it some space to dream and think. Chile, much like its narrowness, a human line between Andes and Pacific, comes with no such thing. Though some Argentines annoyingly associate their European heritage as a racial feature, as an outsider, the part that felt European, once entering Chile, was some degree or safety net for the the bottom of society; a thing of which my current country it seems has none. I follow the route of Granado and Guevara, up Highway 5, though it is almost impossible to believe that this is the same country they rode through.

Where they are hosted in quaint towns, speak of boundless warmth, and seem to ride a rustic dream, I cycle by failed businesses, chased far too frequently by guard dogs, and witness the homelessness, casinos, sports bars and brands of the US social model that I guess must have taken hold here between 1952 and the present. Pinochet and those decades of US-sponsored murder by the state of course comes to mind, but Guevara also writes in his Diaries of a country of grinding poverty, communists driven into exile, the wealth of copper mining and the scarcity of the street brushing up against one another. The government of Salvador Allende, I suppose, was to change all that, although the CIA coup of September 11 1973 had other ideas. I wonder also to what extent the problem arises from a 1952 population of 6 million Chileans and a 2024 population of 19million. Not in terms of resources or nutrition, but did Chile ‐ and of course it is the same question globally - create enough meaning for those new 13million? Were their needs compatible with the contraction and concentration of wealth that happened across the same half century?

I stop in the small town of Los Angeles, where Granado and Guevara spent a few nights awaiting repairs and were hosted at the local fire station. The town is no longer small. I visit the fire station but the notion of asking to stay, as I've considered, is made absurd by the size of the town and the number of homeless people with far more reason to make the same request. People warn me not to walk around late at night. As always, the most prominent word in Latin America seems to be 'cuidado'; be careful, caution. As always, I consider if this is alarmist or simply the word of a continent frequently only a matter of weeks from losing their job, receiving a hospital bill, suffering a crime, or an industrial accident, which is of course only the word for a crime committed by a boss.

On the wall of the fire station next morning, I see graffiti asserting that gender is non-binary. The author condemns the brutal Os and As, the las and els, that so ruthlessly segregate the Spanish language by gender. I weigh that nobody is free until we are all free, how these liberations will help build other liberations. At the same time, I wonder if we broke into an individual consciousness that works against the shared, class consciousness which was the template on which Guevara, the twentieth century, and indeed all successful revolutions, have always worked.