The failure of Silicon Valley Bank is the largest of a banking institution since the 2008 financial crisis, with some $25billion now made available by the Federal Reserve to cover depositors’ losses and hopefully reassure the banking system. Although the word ‘bailout’ is being diligently avoided, the parameters of what have happened are familiar; public bodies are propping-up a failed private bank, investors who were recently selling assets to the unsuspecting pulled their money, SVB’s management sold their shares in their own company before it and the share price was wiped out.

Obvious and specific incompetences explain why this has happened at SVB. The bank had a massive and uninsured risk of exposure to ongoing hikes in interest rates by central banks, which diminished the value of the assets on SVB books. When this risk became apparent and creditors started withdrawing funds, the mismatch between ready funds and ready demands on those funds grew rapidly, leading to investor panic, a bank run, and the collapse of the bank.

Whatever the specific guilt of SVB incompetence, however, it is inseparable from wider economic circumstances created by interest rate hikes at the US Federal Reserve and the major Western central banks. This isn’t to say that central banks should change policy to accommodate incompetence in the banking sector, but it is to say that central banks are maybe doing a disservice by accelerating interest rate rises, their central policy tool, as if in a vacuum where nothing else happens or exists. SVB suggests - unsurprisingly - that 15 years of Quantitative easing and loose monetary policy can’t be undone in 15months flat.

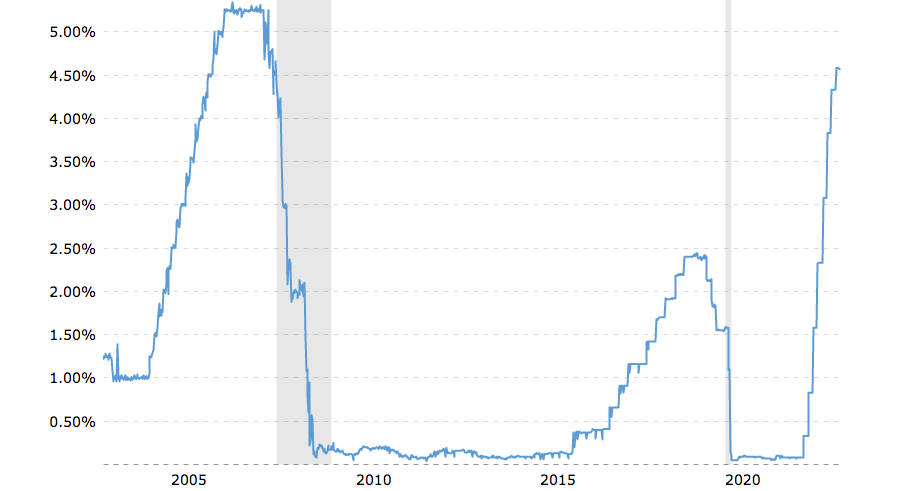

The current central bank approach to interest rates, much like the person with a hammer who sees everything as a nail, has now knocked down its first wall — even if SVB was clearly not a very solid one to begin with. Since the Fed, Bank of England, and ECB began interest rate hikes in spring 2022, bringing about the most aggressive increase in 40 years, there has been a tension between obvious pains emerging in Western societies and economies, and the need to maintain the dogma of central bank independence.

This is not to argue specifically against the idea of central bank independence. There are obvious merits to the argument of central banks acting independently of political interference, but this does not extend to freeing themselves from concerns about the fragility of a creaking economy, or harming the job market (which central bankers - perversely - sometimes argue is a good thing because it makes humans more desperate for work, so reducing wages and thus inflation). It is not strange to believe that central bankers should be independent from political corruption, but this is not to endorse their independence from basic logic, evidence or reason.

The last year, however, and particularly the last few months, seemed to suggest a version of independence free of context or consequences, with central bankers taking near-palpable enjoyment in their willingness to keep hiking, to do whatever it took to - as they saw it - get inflation back in line.

Despite this willingness to talk tough on inflation and interest rates, however, there has been a proportionate reluctance, verging on outright refusal, to associate the discourse on inflation and interest rates with its most central cause: war in Ukraine. Whatever the Russian guilt in the invasion, the West continues - as it did prior to that invasion - to sideline the prospects and therefore chances of the diplomatic resolution that at some point will have to be struck. As well as actively furthering the conflict through the provision of arms to Ukraine, the West has endeavoured to smother the Russian economy, with - given widespread global refusal to uphold US sanctions on Russian energy - limited success.

This is not - whether or not anyone agrees with the policy - in itself an argument against arming Ukraine. It is possible to prosecute a war without sanctioning a belligerent and their exports, though this leads to valid questions of morality if the absence of sanctions causes the prolongation of the war. At that stage then, there remains the necessary question not of morality but of efficacy: will the implementation of sanctions bring an end to the war? One key thing that the West seems not to have reckoned with fully is that sanctions and associated hikes in energy prices might cause a breakdown in consent for the Ukraine war as-quickly among the Western population as the Russian one. If this transpires, it would point to a hubris on the part of Western planners equivalent to that one of central bankers promising to do whatever it takes on interest rates.

This culture of hubris is not the only thing that connects the political class with the politics-independent central bankers who now look likely to back-down on their yearlong threatening of more pain and more rate hikes. Central bank interest rate policy and Ukraine are entwined because the Ukraine policy - war plus sanctions - pursued by the West created the energy price shock that has caused the bulk of Western inflationary pressure. The interest rate policy of central banks has subsequently caused a capital shock by simultaneously increasing the cost of capital.

To put it another way, if the West were going to pursue a Ukraine policy that drastically increased the costs of energy inputs, one way of making this policy more sustainable and durable was not to then hike other input costs, principally, via interest rate increases, the cost of capital. Had the Fed been operating in the interests of wider society, Western foreign policy goals, or even in accordance with the warning-signs coming from the economy, it had an opportunity (and arguably also responsibility) to provide the economy with necessary liquidity to offset the energy price shock. Instead - by fighting energy policy with monetary policy - it has created the second of a twin price shock.

This is where the myth of central bank independence, tasked only with the narrow goal of controlling inflation (to the weirdly specific 2% mark) has proven particularly harmful. Firstly it stokes a culture (if not a cult) where central bankers alone have the ability to control inflation; a notion that significantly relieves politicians of the requirement to do any politics, particularly politics that have a significant ability to alter the cost of living (such as where to war, what to sanction, which harmful practices to tax and which essential ones to subsidise).

The second element of this culture is not just that - once under it - agency for controlling inflation falls entirely to (unelected) central bankers, rather than (elected) politicians, it also centres a sense that the principal or indeed only tool of inflation-control is through interest rates. This obscures the existence of a far greater toolkit of controls - taxes on second homes, rent controls, energy efficiency policies - that are always available to politicians but who choose not to use them, often because they cut against the very vested interests to which politicians are in thrall.

Thirdly, the shibboleth that interest rate hikes have a purely one-way, linear and proportionate relationship to inflation (they bring it down) is - once we take leave of the test tube of central bank ideology - clearly incorrect, as anyone suffering increases in their mortgage, rent, or loan payments will now tell you.

Finally, the idea that interest rates can alone come to the rescue of the inflation now ravaging world and Western publics is a means of obscuring the direct causative relation between the Ukraine war and inflationary pressures, particularly in Europe. Making inflation about only interest rates turns these entwined issues into separate political choices, creating the illusion that we have the luxury of approaching these issues separately.

The collapse of SVB has made it apparent that the pain of such dramatic rate hikes are liable, if continued, to take more banks down with them. Some of what these hikes take down will be bad or at least absurdly careless business models (such as SVB’s). Some of what they take down will be good businesses that need not have failed (exposed depositors or those caught out in wherever the contagion spreads). All this is doubly galling right after a global pandemic that left populations and supply chains shattered and where taxpayers had already paid a significant (though good-value) sum to keep the economy on the rails at all. Unelected central bankers have, in aggressive rate hikes, now mostly collapsed the economic supports and wins of those prudent political decisions taken as the pandemic began in 2020.

It’s easier to say all this than predict what happens next. It seems impossible to believe that the Fed might continue to hike rates at its current rate even as the US banking sector begins to break, with taxpayers again left on the line. While a pause in the interest rate hikes now seem likely (a hypothesis that momentarily unites everyone from me to Goldman Sachs), even this reverse of course harms the veneer of confidence and competence with which the need for rate hikes, and central bank expertise in delivering them, had previously been sold to publics. Whether or not the Fed decision to support a failing bank is correct, the idea of a wider economic situation under control (which is essential to keeping economic situations under control) has been badly damaged.

In order to improve a grave situation, the opening-up of some of the above talking-points is required. If Western publics have been asked to believe that only central banks can control or contain inflation, and through interest rate rises, then the news that central banks are about to stop performing this function requires either conceding that there are in fact other means of controlling inflation, or conceding that the apparently only inflation-curtailing service cannot proceed because we have to prop-up weak banks.

There are no easy answers. Permanently ultra-low interest rates might not have been desirable (though the UK government in particular is guilty of a near-criminal failure to borrow-to-invest during this decade), but that is not to say that their immediate reversal was practical or possible either. Central bank independence can potentially be an estimable idea because checks-and-balances are good for systems, but if the groupthink and hubris is the same between the check and the balance, then that value falls away. Equally, if both parts of the system operate as if in splendid isolation (the state escalates militarily while the central bank escalates fiscally), then this is destined to create discord.

To borrow from the contemporary discourse and realisation that there is no such thing as impartiality in media, likewise where central bankers, economists and financial journalists all graduate through the same institutions and universities, the outcome is less likely to be independence than a slavish devotion to a narrow set of received wisdoms upon which many have clearly become dependent. This, again, could itself be deemed a form of independence (an independence from reality), but whether or not this is in the public interest is another matter.

The neoliberal wisdom that for the last year justified the interest rate policy, indifferent to the economic harm it was doing, rests on the familiar, noxious logic - unexpressed but central - that if it hurts, especially if it hurts publics, then it’s necessary and perhaps even good for you. It is ironic that the same wisdom applied to the post-Soviet period, the ‘shock-therapy’ of IMF reform and privatisation that created first oligarchy and then, inevitably, Putinism, shows quite clearly that Western neoliberalism is slow to learn from its mistakes, nor does it willingly deviate from this take-your-medicine approach to even its own public.

Totalitarianism is often assumed to mean a society of some kind of overt wickedness where dissent is not tolerated. Whether it is in refusal to seriously discuss either the Ukraine war or the interest rate policy, it can just as easily emanate from an overt, banal niceness where no dissent is ventured.